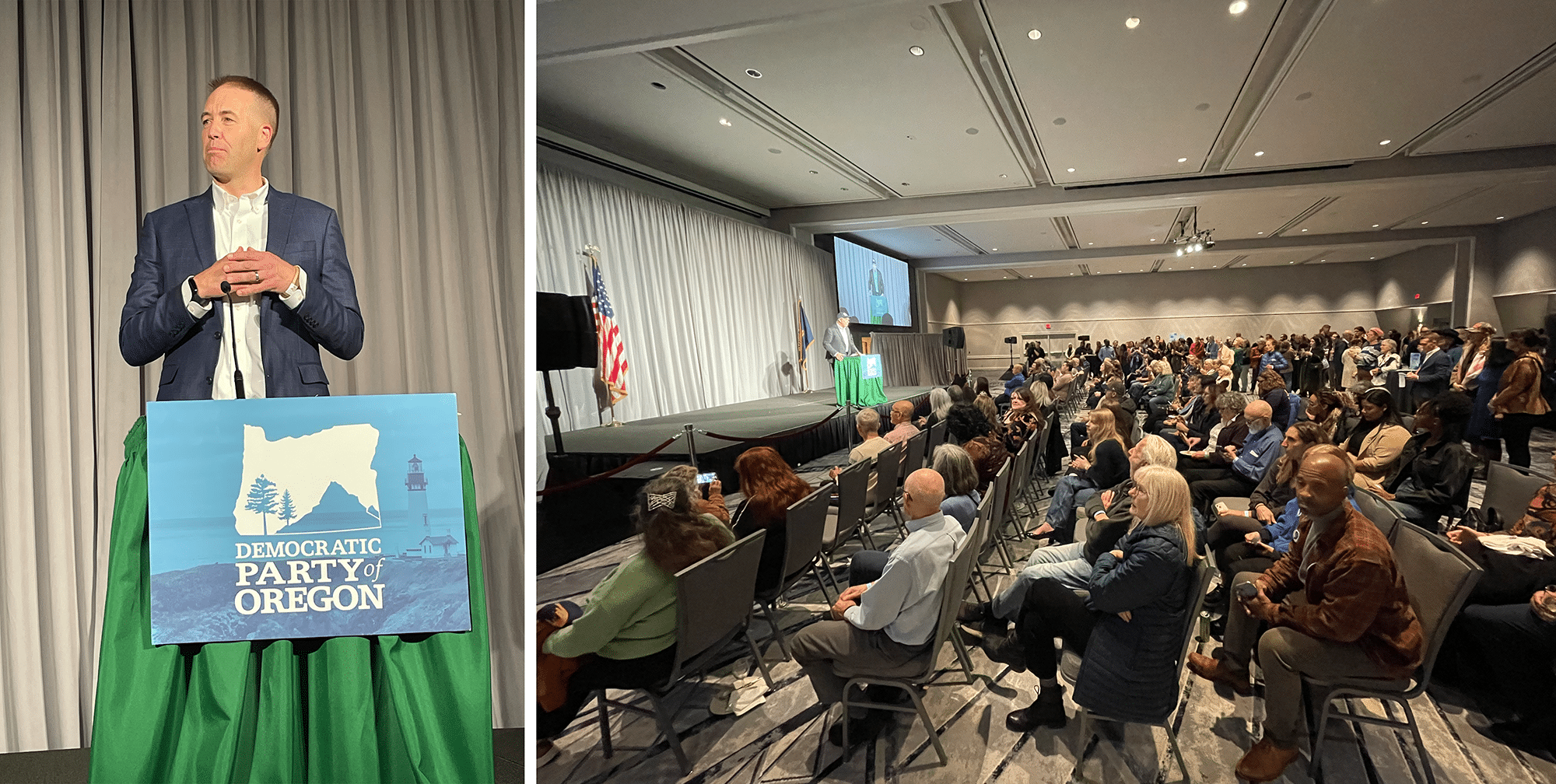

Professional Development Gets ‘REAL’

With just a few weeks until Thanksgiving, activity was buzzing Nov. 13 at Cal-Ore Produce in Tulelake, California where crews were busy packing fresh potatoes for grocery store shelves ahead of the holiday feast.

Countless spuds rode along a maze of conveyor belts to be sorted by size and quality before they were filled into boxes for shipping. Cal-Ore Produce handles roughly 75 million pounds of potatoes every year from four family farms around the Klamath Basin, which are then sold to major retailers including Walmart.

Ryan Finney, of Cal-Ore Produce, leads a tour inside the packing shed where red potatoes are being sorted by grade.

The packing shed was one of several tour stops for REAL Oregon, which kicked off Class 8 Nov. 11-14. REAL Oregon is an acronym for the “Resource Education & Agricultural Leadership Program,” launched in 2017 by the Oregon Agricultural Education Foundation.

The program strives to develop leadership skills through the lens of agriculture, forestry, and natural resource management across the state. Having previously spent 10 years reporting on these issues for the Capital Press and East Oregonian, I was excited to jump back into the field (literally) and translate what I’ve learned into more effective advocacy.

Our first stop was in Klamath Falls and the surrounding area, where we heard from farmers, ranchers, government officials, and tribal members about the basin’s longstanding water conflict and recent removal of four hydroelectric dams along the Klamath River.

REAL Oregon listens to a presentation from Paul Simmons, Executive Director of the Klamath Water Users Association.

Competing Interests

It would be impossible to briefly summarize everything that has led to the current situation facing these Klamath Basin communities.

What it truly boils down to is a demand for water that, as currently regulated, exceeds supply. Driving along Highway 97 north of Klamath Falls, it wouldn’t seem there should be any shortage gazing out at the vast Upper Klamath Lake. But looks can be deceiving.

Farmers rely on water from the lake to fill irrigation canals to grow a variety of crops worth hundreds of millions of dollars annually. At the same time, the Endangered Species Act requires certain water levels for both critically endangered sucker fish in Upper Klamath Lake and salmon in the lower Klamath River. These fish are culturally significant for tribes that have lived in the region since time immemorial.

Add in the need for water to support about 90,000 acres of migratory bird and wildlife habitat within the Klamath Wildlife Refuge system, and you can see how management quickly becomes a delicate balancing act.

Class 8 gathers outside the Klamath Basin National Wildlife Refuge Complex near Tulelake, Calif.

Not to mention, water shutoffs for farms have led to an increase in groundwater pumping, which in turn has resulted in more than 500 domestic wells running dry across Klamath County since 2021.

Listening to a panel of stakeholders and hearing the raw emotion in their voices, it drove home to me how the very fate of families and their livelihoods was at stake. Strong leadership will be required to find lasting solutions, which is exactly what REAL Oregon is trying to accomplish.

Dams Gone

Despite the conflict, interests on both sides have shown they are willing to come together on projects to save fish, rehabilitate wetlands, and ensure a reliable supply of water for farms.

No project has received as much attention as the removal of four dams along the Klamath River, unlocking 400 miles of upstream habitat for salmon.

Overlooking the site of the former J.C. Boyle Dam, it was apparent there is still work to be done re-vegetating the barren landscape once underwater. There was a palpable excitement, however, upon hearing that Chinook salmon had already been spotted swimming in Spencer Creek just months after dam removal, according to the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Overlooking the Klamath River at the site of the recently demolished J.C. Boyle Dam.

Though we didn’t get to see any salmon in the creek for ourselves, we did visit a hatchery operated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service dedicated to rearing shortnose and Lost River suckers. For reasons that aren’t entirely clear, these fish have not had any successful reproduction in Upper Klamath Lake since the 1990s, and their numbers are now crashing.

Meanwhile, Scott White, General Manager of the Klamath Drainage District (KDD), discussed his district’s effort to “re-plumb” the basin, reworking irrigation canals to boost water for the Lower Klamath Lake National Wildlife Refuge.

None of these projects alone will solve all issues in the Klamath Basin. However, it was heartening to see that there’s still a thirst for collaboration and compromise. I look forward to continuing to learn through REAL Oregon how I can help these hardworking leaders who are making a difference

Pac/West’s George Plaven, with classmates Ryan Tuthill (center) and Austin McClister.